Public access and secrecy

Most universities and other higher education institutions in Sweden are government authorities and therefore subject to the Swedish principle of public access to information (offentlighetsprincipen). This principle also applies to some universities that are not formally government authorities. As a result, all employees must understand what the principle of public access to information entails and how it affects research activities.

The principle of public access to information

The Swedish principle of public access to information means that the public and the media have the right to transparency in the activities of the state and local authorities. The principle is a collective term for several rights, all of which are protected by the Swedish Constitution. This constitutional status gives them strong legal protection and makes them difficult to restrict.

The principle of public access to information includes the following rights and freedoms:

- Public access to official documents: Anyone has the right to read official documents held by public authorities, unless the documents are subject to secrecy.

- Freedom of expression and the right to communicate information: Public employees generally have the right to provide information to the media (e.g., newspapers, radio, and television) for publication, or to make information public themselves.

- Public access to court hearings: The public and mass media have a right to attend trials.

- Public access to meetings of decision-making assemblies: The public and mass media have a right to attend when for example the Swedish Parliament (Riksdagen), municipal assemblies, and regional assemblies meet.

The principle of public access to information promotes open public debate and gives Swedish citizens insight into the activities of public authorities. The transparency it provides also facilitates media oversight of public institutions, which in turn contributes to more efficient administration, reduced influence from improper interests, and lower levels of corruption.

Public access to official documents

Public access to official documents (handlingsoffentlighet) is one part of the principle of public access to information and it is protected by the Swedish Constitution. It means that everyone has the right to request and access official documents held by public authorities. However, not all documents held by an authority are classified as public, and not all public documents are accessible – some may be subject to secrecy.

Access to official documents is regulated in Chapter 2 of the Freedom of the Press Act (tryckfrihetsförordningen, SFS 1949:105, TF), while secrecy is governed by the Public Access to Information and Secrecy Act (offentlighets- och sekretesslagen, SFS 2009:400, OSL). The links go to the legislation in Swedish; an official outline in English of both acts can be found in the document Public Access to Information and Secrecy (PDF).

The Archives Act

The Archives Act (arkivlagen, SFS 1990:782) (link to the legislation in Swedish) defines which public and official documents must be preserved and when they may be disposed of (destroyed). Public authorities may not dispose of official documents without support from legal provisions governing disposal. The archival framework requires authorities to preserve, organize, and manage their public documents to ensure the right of access to official documents, the availability of information for the legal system and public administration, and to meet the needs of research. The transparency provided by the principle of public access to information would be meaningless if there were no documents available for scrutiny. For this reason, the requirements of the Archives Act are a key component of the public access system.

Official documents

To understand how the principle of public access to information functions in the context of research, it is important first to clarify what is meant by an official document (allmän handling).

According to Chapter 2, Section 3 of the Freedom of the Press Act, a document is “a presentation in writing or images, or a recording that can be read, listened to or apprehended in some other way only using technical aids” (official translation from Public Access to Information and Secrecy). This means that a document may be a written record – something that can be read directly – an image, or a recording such as an audio or video file that requires a device for playback.

As a result of this definition, much research material qualifies as documents. However, there are also types of research material that are not documents. One example is human biological material, such as blood samples, tissue or other physical specimens from the human body. The sample itself is not a document, but any values resulting from analysis of the sample become documents when they are recorded – for example printed out from an analysis machine or entered into an electronic system.

A document is not automatically subject to the principle of public access to information. To request a document, it must be a public, official document.

A document is official if it is held by a public authority, and considered to have been received or drawn up by an authority (Chapter 2, Sections 4, 6–10 of the Freedom of the Press Act, TF).

A document is received (Section 9, TF), when it has been sent to the authority by an external party, for example via post or e-mail, or has otherwise reached the authority. For electronic documents, this applies as soon as the file reaches the computer of the official dealing with the document. A document does not have to be registered or recorded in order to be received, and therefore an official document.

A document is considered to be drawn up (Section 10, TF) when it has been managed and completed at a public authority, and dispatched (or sent out) from the authority, made available (e.g., uploaded to a registry or website), or otherwise finalized when the matter to which it relates is closed by the authority. In the Freedom of the Press Act, there are specific rules for when a document is considered drawn up, but the general principle is that a document becomes official once it reaches its final form.

Preliminary drafts and documents still in progress, as well as memoranda (notes), are considered working material and not official documents if they have not been retained for archiving.

A document is considered held by a public authority if it is physically located in the authority’s systems or archives. A document can also be logically held – for example, if it physically resides with another authority but is accessible via a shared database. A common example is the LADOK student records system: if University A can access LADOK records stored by another university, those records are also considered held by University A and therefore constitute official documents there. The public thus has the right to access such documents, provided they are not subject to secrecy.

Research material as official documents

Research conducted at Swedish universities and higher education institutions forms part of the public authority’s activities and is therefore subject to the principle of public access to official documents. As a rule, all research-related documents are official documents. However, the point at which a document becomes official varies depending on its type.

For example:

- Surveys used for data collection become official, drawn up documents once they are finalized for use.

- Completed surveys filled in by research participants become official, received documents when they are returned to the researcher or submitted electronically.

- Recorded analysis results from blood samples become public documents immediately when they are recorded.

- Photographs or audio/video recordings made or collected during research are considered completed once the photo is developed or the recording ends.

The principle of public access to information means that the public has the right to access official documents unless those documents are subject to secrecy. If a public document is eligible for disclosure, the authority must provide access immediately or as soon as possible on site or by providing a copy. Some documents are immediately accessible; others may require retrieval from an archive, database, or may need redaction of sensitive content before release.

Access on site means that the person requesting access to a document must be given the opportunity to read, listen to, or otherwise take part of the document where it is available. If the document requires a technical aid to be read, viewed, or listened to, the authority must also make that equipment available. Alternatively, a copy may be provided – again, as quickly as possible. In some cases, a fee may be charged in accordance with the Fees Ordinance (avgiftsförordningen, SFS 1992:191) (link to the legislation in Swedish).

It is important to understand that the right to access official documents means a right to request access. Authorities are not required to proactively publish all official documents – for example, in libraries or on the internet. In fact, doing so could be unlawful in certain cases, for example when the material is protected by copyright.

Documents that are not public do not need to be disclosed. This includes documents not held by the authority, private letters, unopened tenders (which become official and public only at the official opening time), and files stored purely for technical backup or temporary storage. Drafts, memos, periodicals, and items held as part of a library collection are also not considered official documents.

When handling a request for access to an official document, consider the following:

- Is it a document?

- Is it an official document?

- Is the document open or secret – is there legal justification under the Public Access to Information and Secrecy Act for withholding it?

Secrecy

Although the principle of public access to official documents is the main rule, there are exceptions where the public does not have the right to access certain information. A university may only deny access to research data if the data are covered by a secrecy provision in the Public Access to Information and Secrecy Act.

Every time a request for disclosure of a document is made, a secrecy examination (sekretessprövning) must be carried out. Researchers should already have an idea of whether their material may be subject to secrecy when the data collection begins. The secrecy examination involves determining whether any provision in the Secrecy Act (OSL) applies to the requested information. It may also require an assessment of whether disclosure could cause loss or damage to an individual. Here, loss refers to economic loss, and damage refers to various types of infringements of privacy, such as reputational damage or distress if sensitive personal information should be disclosed.

This means that the same document might be considered secret in one situation but not in another, depending on who is requesting access and for what purpose. In some cases, a document may be disclosed with reservations, for example under conditions that the information is not published, or otherwise kept confidential.

When weighing the public’s interest in access against the individual’s right to privacy, the latter must sometimes take precedence. In such cases, the information may be withheld on grounds of secrecy.

What does secrecy mean?

The term secrecy is defined in Chapter 3 of the Public Access to Information and Secrecy Act (OSL) as a prohibition on divulging information whether orally, by disclosing an official document, or in some other way (for instance, through the disclosure of a document that is not an official document, or the production of an object).

In a research context, secrecy is relevant in two ways: It governs when and how researchers and the public may access other researchers’ data, and it provides a framework for protecting sensitive information collected by researchers.

A document is only considered secret, and thus possible to withhold, when there is a specific secrecy provision in the Secrecy Act that supports secrecy. This means a researcher cannot promise that the information is secret if there is no such legal basis. Types of information that may be subject to secrecy include, for example:

- Information concerning an individual’s health or sex life, such as data on illnesses, addictions, sexual orientation, gender transition, sexual offences, or similar, where it must be assumed that disclosure would cause serious detriment to the individual or a close relative (Chapter 21, Section 1).

- Information from psychological studies conducted for research purposes, unless it is clear that disclosure would not cause loss or damage to the individual or someone close to them (Chapter 24, Section 1).

- Information about a person’s business operations, inventions, or research findings provided or obtained through collaborative research with a private actor, where it must be assumed that participation was conditional on confidentiality (Chapter 24, Section 5).

- In the health and medical care sector, information about a person’s health or other private matters, unless it is clear that disclosure would not cause loss or damage to the individual or someone close to them. (Chapter 25, Section 1).

When a request for an official document is received, the secrecy examination is carried out by the authority that holds the document. If the document falls under one of the Secrecy Act provisions, it must be assessed whether it can be released in full or in part. Sections of a document that are not covered by a secrecy provision must be released under the same rules that apply to official documents.

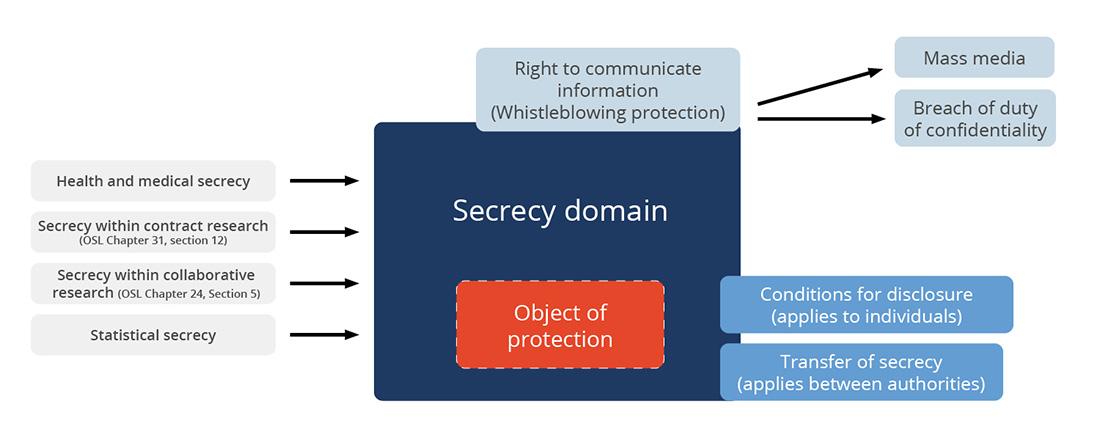

Secrecy domains

A secrecy provision typically applies to a specific domain. These might include health and medical care, social services, the Swedish Migration Agency, or a university. For example, a university may not apply secrecy rules intended for the Migration Agency, because the institutions fall under different secrecy domains. Similarly, universities do not apply healthcare secrecy rules unless the data in question originate from health and medical care and the secrecy is transferred with the data. Secrecy may also apply between different public authorities – or even between different departments within the same authority.

Within each secrecy domain, what is protected is known as the object of protection. For example, in health and medical care, the objects of protection are patients.

Two other concepts are important: Conditions for disclosure (sekretessförbehåll) and transfer of secrecy (överföring av sekretess).

A condition for disclosure is a restriction placed on how a recipient may use secret information. This applies only to private individuals. For instance, an authority may release data on condition that they are not distributed or published, or that they can only be published if they are anonymized. A public authority may not attach such conditions when releasing documents to another authority. Once received, the documents become part of the second authority’s official documents and are subject to a new, independent secrecy examination if there is a request for disclosure.

Transfer of secrecy means that secrecy follows the data from one authority to another. For example, health and medical secrecy may still apply to data used in a university research project, if those data originally came from the health and medical care – even though the university does not itself belong to the health and medical care confidentiality domain.

Types of secrecy

There are three levels of secrecy: absolute secrecy, strong secrecy, and weak secrecy.

Absolute secrecy: No information may be disclosed, except to staff who need it for their work. No examination of damage is required. Some exceptions may apply where disclosure is mandated by law.

Strong secrecy, with a reverse requirement of damage: As a general rule, documents are secret. Information may only be disclosed if it is clear that doing so will not result in loss or damage. This means there must be a high degree of certainty that no loss or damage will occur if the information is disclosed.

Weak secrecy, with a straight requirement of damage: As a general rule, documents are public. Information may only be withheld if there is a reasonable assumption that loss or damage could result if the information is disclosed, for example if there is a known factor suggesting that disclosure might be harmful.